5 READ-TIME

Grasshopper Identification Leads To Better Pest Control

January 9, 2024

By Trevor Bacque

Just the name alone — grasshoppers — can strike a near-universal fear into the heart of any farmer. But how much do you know about them, really?

It could be that fear is often misplaced — after all, of the 100-plus grasshopper species across the Prairies, 95 per cent are completely harmless to your crops. Only a rotating halfdozen or so give cause to fret, so it’s worth learning a thing or two about these insects.

Dan Johnson, University of Lethbridge professor of geography and environment, and self-described grasshopper hobbyist, says the overwhelming majority of hoppers are either beneficial in the ecosystem as food for many bird species, or simply neutral. In other words, not all grasshoppers need to be removed, and many should be left alone.

Improving your grasshopper knowledge can help you create tailored solutions for a stronger, integrated pest management plan, and also may help dial back the anxiety upon finding a hopper hotspot during the growing season.

THE MONTH MAKES THE DIFFERENCE

Johnson has faithfully collected specimens and compiled vital information related to hoppers and other insects for more than 40 years, much of it in his spare time.

He says that, in terms of agricultural production, only a trio are currently worth paying attention to: the twostriped grasshopper, Bruner’s spurthroat grasshopper and the clear-winged grasshopper. The Carolina grasshopper has been an issue on the Prairies in the past, and while it hasn’t been for many years now, it still catches negative flack because it is large, highly visible and a strong flyer.

Johnson says the easiest and most dependable test to know if you need to take action is to answer a simple question: What month is it?

“Any grasshopper flying before June is not a pest,” says a resolute Johnson. “If they have coloured wings in flight, if they crackle, if they sing, if they have a long, pointed egglaying ‘stinger,’ or if active before the end of May, no problem on the Canadian Prairies.”

1: The Bruner’s spurthroat grasshopper is usually found in higher elevations in Alberta’s foothills and Cypress Hills. Recently it has been increasing in numbers in the Peace Region.

2: Bruner’s Spur-Throat – Embryos

3: Two-striped grasshopper eggs

4: Possible very young two-striped grasshopper

PHOTOS: DAN JOHNSON

So, those grasshoppers you see, with highly visible hind wings when in flight that are red, yellow, orange or black, are not crop pests.

“Crop pest grasshoppers hatch in late May and early June, are tan, brown, or black, and always have tiny triangular wing buds, not large wings that can be folded back when examined closely,” explains Johnson. And no, he says, weather doesn’t matter; cold temperatures rarely affect grasshoppers that overwinter in the soil.

If you spot a pest species in rangeland, on headlands or other grasslands, you can almost assuredly rest easy that it won’t move into the crop, which may not be of comfort to hay growers. “Monitoring during warm weather will allow this to be determined because, in some cases, the crop pest species will also move into pastures and hay,” Johnson cautions.

SCOUTING AS ART AS WELL AS SCIENCE

The importance of scouting cannot be underscored enough, and that’s partly because crop pest grasshoppers are silent — who knew?

For those grasshoppers that do damage crops, there are rules of engagement, says Johnson. The first, cheapest and often most effective method to determine whether a spray is necessary is to simply walk through your fields. As a general rule, less than 10 grasshoppers per square metre is not a problem in most crops. However, Johnson has seen extremes where fewer than 10 hoppers per square metre do a lot of damage, and more than 60 do no damage at all.

Effective monitoring is part art, part science. “Picking some up and seeing if they seem mature helps,” he says. “If there is no crop damage, no control is needed. Treating only strips or edges works in many cases. We have cellphones and Internet to send photos now, so information is much more available than in previous outbreaks.”

Also, it’s important to remember that certain invasive grasshoppers prefer certain crops. Again, this can make knowing if it’s time to spray a bit of a challenge, so it pays to investigate up close. For example, clear-winged grasshoppers don’t eat canola or peas, but it can certainly be startling to see a swarm move in on these crops after July.

5: A one day old black and white clear winged grasshopper.

6: Adult black and white clear winged grasshopper.

7: Young two-striped grasshopper.

8: The two-striped grasshopper is dark green and yellow and prefers to walk rather than fly. This species along with the Bruner’s spur-throat and the clear-winged grasshopper are cause for concern for Prairie farmers.

9 & 10: The Carolina grasshopper is a large, strong flyer and has been an issue in the past for Prairie growers.

PHOTOS: DAN JOHNSON

The Carolina grasshopper (top) is a large, strong flyer and has been an issue in the past for Prairie growers. The two-striped grasshopper (bottom) is dark green and yellow and prefers to walk rather than fly. This species along with the Bruner’s spur-throat and the clear-winged grasshopper (Page 19) are cause for concern for Prairie farmers.

If you see feeding damage, and if the threshold count is high enough, spraying is the only viable control option, and timing is absolutely critical — the insecticide must contact the hoppers.

“If spraying is too early, grasshoppers that are still in the ground are not controlled,” says Johnson. No studies into the economics of spraying grasshoppers have been completed since the ’90s, he says, which means grasshopper knowledge, efficacy and best management practices are, at best, rules of thumb.

Above all, Johnson encourages farmers to not overreact, as hard as that may be at times. “With grasshoppers, they can’t poison the crop,” he says. “They can’t do anything like that. They can’t go underground. They only chew. So, what you see is what you get. If you do a little extra monitoring and you don’t see any crop damage, you can just hold off.”

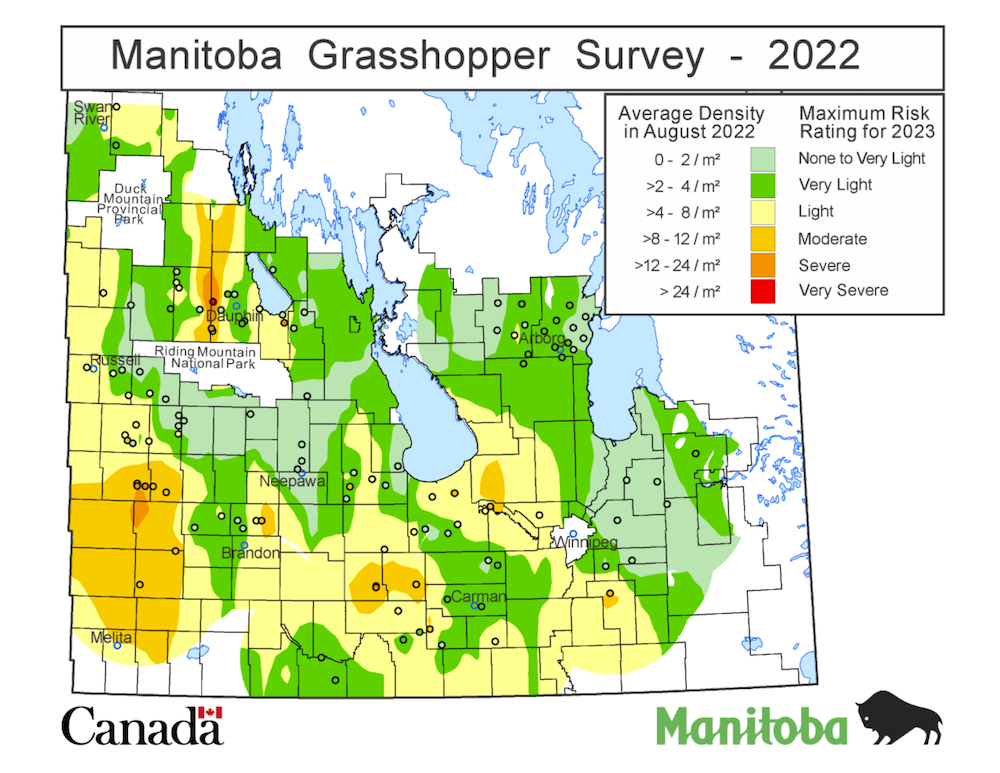

MAP it OUT

Across the Prairies, grasshopper maps let farmers go back in time and see how accurate the maps were as well as the insects’ movement patterns.

Typically, ag fieldmen count breeding populations and make a hypothesis for the springtime, so it’s important to remember that forecast maps only show the potential for a grasshopper outbreak since the previous summer’s counts are based on mature species observed.

“In the north, this does not mean hatchlings will appear in the spring,” says Dan Johnson. “But in areas from Edmonton to the U.S. border and over to Saskatchewan, high numbers of mature grasshoppers on the map usually mean eggs could have been laid, so a warm dry spring would help them to survive.” Such a spring is ideal for grasshoppers, allowing them to hatch and mature faster, especially if there are no fungal diseases around that might kill them.

In Alberta, research has shown that most species have a oneyear lifecycle. However, the Bruner’s spur-throat grasshopper has been determined to have a two-year cycle, based on 14 years of data, according to the Alberta government. Farmers in the Peace Region and north-central Alberta should be watchful for this species.

Luckily, through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a study of grasshopper species, timing, parasitism, historical trend, impacts of weather, and even DNA comparisons is underway in the Peace Region.

FRIEND or FOE?

Currently, the top two offending grasshoppers on the Prairies are the clear-winged and two-striped. Here’s how to tell them apart from “the friendlies.”

| FOE | |

|

CLEAR-WINGED GRASSHOPPER: a good flyer that glistens yellow in flight. When at rest, it has a tan colour and large spots. |

|

TWO-STRIPED GRASSHOPPER: fat, dark green and yellow, this hopper flies if the weather is hot, but mainly prefers to walk. |

| Friend | |

|

Club-horned grasshopper: emerges in March and is strictly bird food. |

|

Marsh meadow grasshopper: While it can be seen at roadsides singing and scratching, this one is completely harmless. |

|

Velvet-striped and brownspotted range: Since both these grasshoppers overwinter in an active form, they’re out very early in spring. Both are only for the birds. |

|

Obscure: While common on native grasses, this is a completely neutral hopper. |

|

Turnbull’s grasshopper: Perhaps a farmer’s best friend, this hopper voraciously eats weeds – Russian thistle, lamb’s-quarters and kochia chief among them. |