4 READ-TIME

Managing Clubroot in Canola

May 29, 2021

Clubroot in Canola

Clubroot, caused by the soilborne protist Plasmodiophora brassicae, is a serious and destructive obligate parasitic disease in canola and other cruciferous crops such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, cabbage, and mustard (Figure 1). Weeds such as stinkweed or field pennygrass (Thlaspi arvense), Shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris), flixweed (Descurainia sophia) and those in the mustard family are hosts for the disease. A protist is an organism that has plant, animal, and fungal characteristics. An obligate parasite is completely dependent on its host plant for nutrition, reproduction, habitat, and survival.

Figure 1. Clubroot galls on canola roots. Leduc, ND (2018) Bayer owned picture. Xuehua Zhang.

Clubroot was an identified problem in cruciferous vegetable crops for several years in Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Atlantic Canada prior to being identified in canola.1 In 2003, clubroot in canola was confirmed in fields near Edmonton, Alberta and has since spread throughout the canola growing areas of Canada and into North Dakota in the United States (2013).2,3 In 2007, P. brassicae. was declared a pest in Alberta resulting in the Alberta Clubroot Management Plan. In 2020, over 3,000 fields across Alberta had incidence levels ranging from below 30 and above 60 percent infestation.1

Potential yield loss is dependent on the time of infection, soil moisture, soil temperature, spore load, soil pH, soil type and texture, host genotype, pathogen pathotype, and other factors. Should the disease develop early under favorable conditions with moderate to high spore load, a 100 percent yield loss is possible. Low spore loads and poor environmental conditions for disease development may result in little or no yield loss.1 Canola research in Sweden found that if a field was nearing 100 percent infestation, a yield loss of about 50 percent could occur. Additionally, infestations of 10 to 20 percent resulted in 5 to 10 percent yield loss.2

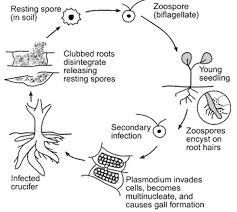

Life Cycle (Figure 2)

Long-lived (can survive up to 20 years) soilborne Plasmodiophora brassicae resting spores, stimulated by exudates from canola roots, germinate in the spring and produce zoospores that swim in soil water to canola root hairs. Infection occurs through the hairs or other wounds. The pathogen then forms an amoeba-like cell that multiplies, joins like cells, and forms a protoplasm mass with many nuclei. The mass divides to form many secondary zoospores that are released into the soil. The secondary zoospores re-infect the original host and close by plants and invade the interior of the root. Again, the amoeba-like cells multiply, form another mass which can alter plant hormones causing the cortical root cells to swell and form clubs or galls (Figure 3). Within the galls, new resting spores are produced. As the galls decay, millions of spores are released into the soil.2

Figure 2. Lifecycle of Plasmodiophora brassicae. Permission granted for use by Dr. Sally Miller, The Ohio State University. Graphic from The Ohio State University. Permission granted to use granted by Dr. Miller.

Figure 3. Clubroot galls on canola roots. Alberta, Canada (2017). Bayer owned picture_Xuehua Zhang.

Favourable Environment

- Warm soil (20 to 24°C)

- High soil moisture

- Acid soil (pH less than 6.5)

Pathogen Movement

The resting spores can move to new locations with free-flowing water, wind, contaminated machinery, and on the feet of wildlife and mankind. Therefore, it is important to reduce the opportunity for water and wind erosion, and to clean equipment, shoes, and boots before leaving an infested field. Managing wildlife is not practical, but anyone hunting on infested fields should be asked to clean shoes and boots before moving to another location. Hunting dogs should have their feet cleaned too!

Symptoms of Infection

Clubroot infection can mimic other agronomic problems; therefore, plants must be dug up to evaluate the roots for gall formation. The galls absorb water and nutrients and inhibit their transportation through the plant causing seedlings to wilt, become stunted, and turn yellow (Figure 4). These symptoms can mimic nutrient deficiencies, other diseases such as blackleg or Fusarium wilt, drought or water-logging or insect injury. Late season infection may lack seedling symptoms, but the plants ripen prematurely causing seeds to shrivel. If plants are dug near maturity, the galls may have deteriorated, turned brown, and be difficult to see compared to the earlier white gall colour.2

Figure 4. Canola yellowing associated with clubroot. Leduc, ND (2018). Yellowing can be caused by other agronomic factors; therefore, root observation is a must for clubroot identification. Bayer owned picture_Xuehua Zhang.

Canola Product Resistance

Many pathogens, including Plasmodiophora brassicae, can develop new pathotypes or strains. As of February 2021, 36 P. brassicae pathotypes (strains) have been identified and are likely to increase.4 Currently, clubroot resistant canola hybrids are available for many of the strains of clubroot. Some new clubroot resistant hybrids on the market contain more or different sources for clubroot resistance; this is known as “next generation resistance.” If canola hybrids, with original source resistance continue to perform well in fields with known clubroot populations, the planting of next generation resistance may not be required yet. However, it is important to send soil and plant samples to laboratories approved for clubroot identification to confirm the presence of clubroot and if possible, have the clubroot pathotype identified. Next generation resistant products should be planted accordingly and used along with other best management practices to help manage and reduce spore production.

Management

- Scouting should be a weekly practice during every cropping season to increase the awareness of any disease development, insect activity, weed growth, fertility deficiencies, chemical injury, and other agronomic issues. If poor plant health is an issue, they should be examined above and below ground to identify the cause. Shoes and scouting equipment should be cleaned before going to another field. Scouting should include scouting rotational crops for clubroot susceptible weeds.

- Crop rotation is crucial for managing this disease and can help reduce the opportunity for infestation in “clean” fields and potentially help reduce the negative impact of clubroot if already present. Rotating away from canola to crops that are not clubroot hosts can help reduce spore production.

- In areas where clubroot has been identified, equipment should be cleaned before leaving one field for another to help reduce the potential for spore movement. Shoes and boots should be cleaned too. When travelling off-farm, be mindful of potential opportunities to carry clubroot spores onto your farm.

- Establish waterways and other conservation measures to help reduce runoff and wind erosion.

- Plant clubroot-resistant canola hybrids if the field or neighboring fields are known to have clubroot spores. If clubroot has been identified in your county, clubroot resistant hybrids should be considered. Rotate away from canola for a minimum of two years (1 in 3-year crop rotation) to help lower soil spore load and reduce clubroot pathotype resistance. Because of clubroot pathotype resistance, plant an adapted canola hybrid with another source(s) of resistance when canola is planted again. A two-year break from canola can result in a 90% reduction in the production of clubroot resting spores.2

- Weeds that are clubroot hosts should be controlled. Volunteer canola in rotational crops should be controlled to help reduce the potential for additional spore production.

- Manage field patches where clubroot has been identified. Avoid tilling and other field operations through the patch as spores can be transported, increasing the patch area and potentially infesting new areas and fields. Consider planting the patches to grass to hold the soil in place. Applying lime to the patches may help reduce gall size and limit spore concentration. In some situations, soil fumigants can be used to kill the resting spores; however, other beneficial soil microorganisms can be killed too.

Sources

1Barnes, A. Clubroot. Canola Encyclopedia. Canola Council of Canada. https://www.canolacouncil.org/canola-encyclopedia/diseases/clubroot/

2Hartman, M. 2015. Clubroot disease of canola and mustard. AGRI_FACTS. Practical Information for Alberta’s Agriculture Industry. Agdex 140/638-1. Alberta Government. www.agriculture.alberta.ca.

3Chittem, K., Mansouripour, S.M., and del Río Mendoza, L.E. 2014. First report of clubroot on canola caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae in North Dakota. Plant Disease. Vol. 98, No. 10. The American Phytopathological Society. https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/10.1094/PDIS-04-14-0430-PDN.

4Barnes, A. 2021. Clubroot. Canola Council of Canada.

Legal Statements

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Performance may vary from location to location and from year to year, as local growing, soil and weather conditions may vary. Growers should evaluate data from multiple locations and years whenever possible and should consider the impacts of these conditions on the grower’s fields.

DEKALB® is a registered trademark of Bayer Group. Used under license. ©2021 Bayer Group. All rights reserved. 1026_S4_CA