4 READ-TIME

Corn Stalk Rot

May 9, 2021

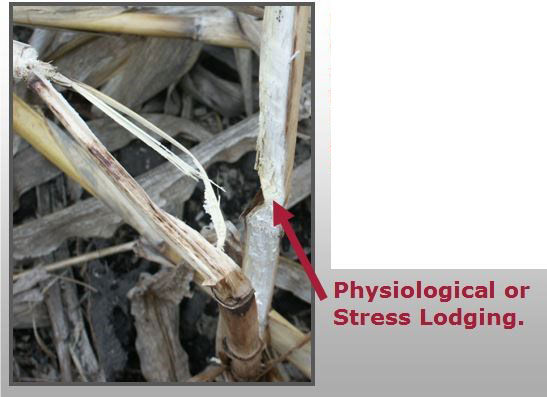

Stalk rots in Eastern Canada are primarily caused by three fungi: Anthracnose, Gibberella, and Fusarium.1 Although disease severity varies each year, plants become prone to infection when nutrients are remobilized from stalks to ears (cannibalization). This in turn, leads to weakened stalks which are prone to lodging.

Stalk Rots

Common stalk rot diseases in corn caused by fungi include Gibberella, Fusarium, Anthracnose, and Diplodia. Stalk rot caused by species of Gibberella, Fusarium, and Diplodia are not usually apparent until several weeks after silking and pollination, whereas Anthracnose symptoms are generally not evident until the corn plant starts to die. Nutrient movement is greatly compromised from the infection process, and yield losses of 10 to 20% can arise from poorly filled ears and harvest loss due to lodging.1

Stalk rot symptoms first appear as the leaves turn a dull gray-green, similar in appearance to frost or drought damage. In just a few days, the leaves turn brown. The lower internodes turn from green to tan, straw-colored, or dark brown and are spongy and easily crushed. When stalks are split lengthwise, only the vascular strands remain intact with the pith tissue disintegrated and discolored.

Gibberella. Stalks infected with Gibberella have a characteristic pink to reddish discoloration of the pith and vascular strands (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gibberella infected pith.

Fusarium Stalk Rot. Fusarium stalk rot appears similar to Gibberella, except that the discoloration of infected tissues commonly varies from whitish pink to salmon. Fusarium stalk rot is often diagnosed in the absence of symptoms of other stalk rot pathogens (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fusarium stalk rot.

Anthracnose Stalk Rot. A shiny black or dark brown discoloration of the stalk late in the season is typical of Anthracnose. This black discoloration usually extends up the stalks for several internodes. The pith is usually dark brown and decayed (Figure 3). Severely affected stalks are likely to lodge.

Figure 3. Anthracnose infected stalk and pith

Diplodia Stalk Rot. This rot has also been found in the area and is distinguished from other stalk rot diseases by the numerous, tiny, raised black dots (pycnidia) produced by the fungus clustered on or near the lower nodes of infected stalks. These black dots are embedded in the stalk and cannot be scraped off with a fingernail (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Diplodia infected pith

Disease Development

Development of stalk rot is generally favoured by early-season environmental conditions that promote kernel set followed by late-season stress. Post-pollination stresses may include:

- An excess or lack of moisture

- Nutrient deficiency or imbalance

- Excessively cloudy weather

- Insect, hail, or other invasive injury to the leaves, stalks, or roots.

Extended periods of very dry or wet weather prior to pollination, followed by an abrupt change for several weeks after silking, favour the development of most stalk rot fungi.

Stalk Cannibalization

Stalk cannibalization occurs when the corn plant is not able to complete ear fill without remobilizing nutrients and energy stored in the stover. This often occurs when aggressive corn hybrids quickly develop large ears. As maturing kernels accumulate carbohydrates late in the season, nutrients in the plant may be in short supply.

Nutrients and energy are often remobilized from lower leaves and stalks to meet the demand from the developing kernels. The lower portions of the plant become less competitive for these nutrients, resulting in weakened stalks and roots, which are more susceptible to stalk rots.

For example, stalk cannibalization can be seen with a late infection by gray leaf spot (GLS). When good yield potential is set, and GLS infects late, the disease decreases the photosynthetic capacity of the plants. With high yield potential and less photosynthetic ability, the corn plants are going to take energy from the root base, stalks, and leaves to finish filling the ear.

Scouting Corn for Lodging Potential

Two methods of scouting for stalk rots can help determine if early harvest is necessary. For either method, select 20 plants from five different locations in the field for a total of 100 randomly selected plants1.

Push Test. The top portion of plants are pushed 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 inches) from the vertical. Numbers of lodged plants are noted.

Pinch or Squeeze Test. The area above the brace roots is squeezed (lower leaves removed if necessary). Numbers of rotted stalks are noted.

When 10 to 15 percent of plants are found to lodge or are rotted, consider slating the field for earlier harvest. Do not wait until the combine is in the field to find you have late-season stalk lodging. Now is the time to be looking at fields to identify problems that may become worse if appropriate action is not taken.

Early Harvest

Severely damaged plants will likely not remain standing until the normal harvest period. Therefore, preparations need to be taken to harvest problem fields early. Although high grain drying costs may be a concern when harvesting wet grain, this expense will likely be a better option compared to the loss of yield due to increased lodging later in the fall.

Figure 5. Stalk lodgin in fall due to cannibalization and stalk rots.

Figure 6. Characteristic symptomology for physiological stalk lodging, including pinched stalk and white pith.

Please consult with your DEKALB® Brand Seed Agronomist if you have questions about stalk rots or late-season lodging in your fields.

Sources:

1 OMAFRA. 2011. Publication 811. Diseases of field crops: corn diseases.

University of Illinois Extension. 1995. Corn stalk rots. RPD No. 200.