As you prepare for one of the most important tasks this season, make sure your spray equipment and your software are up to snuff

As spraying season approaches, it’s vitally important to be prepared and ready to go. But how? Tom Wolf, sprayer specialist at sprayers101.com offers insights into the latest trends and tips for a successful #spray24.

There are typical checklists that Wolf recommends but he says the first thing to do, before getting into the equipment shed or the field, is download any relevant software updates. Ensure you’re on the latest version of your software and double check that your field maps are loaded and working well. It’s a simple task, but a hugely important one because glitchy maps or old software could derail your entire spray season.

Once that’s done, it’s time to get on with the equipment itself.

Recirculating booms

If you haven’t already heard, you have now. Recirculating booms are worth it. Prices vary, but $10,000 to $15,000 affords you a retrofit kit, which are now also being sold direct from certain manufacturers, that Wolf labels “absolutely worth it” and “a no-brainer.” Other companies sell individual components based on your needs, to make a DIY recirculating boom.

The value of a recirculating system is that it prevents residue from lodging in dead spots, such as boom ends. A small change to the plumbing lets you prime and flush the boom without spraying, avoiding waste and contamination.

One common issue is when dry products become lodged where the flow comes to a dead end. That is not an issue with a recirculating boom. “It means you can get started and finished faster because you’re not as worried about the boom ends,” says Wolf. “That messy boom-end flushing step is basically eliminated.”

While most booms have five to 13 sections, all independent of each other, a recirculating boom strings them all together in three large sections; left boom, right boom and centre rack.

“Each one of those is fed, not from the middle, but from the far end. That means it’s a linear line from the far end in towards the sprayer,” explains Wolf. “The boom becomes, basically, a part of the tank’s plumbing.”

Typically, farmers must run a boom for a couple minutes to make sure all boom ends are loaded with product. Now, product is simply pushed through the boom without spraying a drop. “We could even do that in many cases while driving to the field; you unfold the boom and you’re ready to go.”

A Bilberry green-on-green camera system mounted on an Agrifac sprayer. Cameras are spaced three metres apart, and the images are processed by a computer mounted on the boom. The computer can analyze an image 30 times per second, offering a spray-or-no-spray decision within 150 milliseconds.

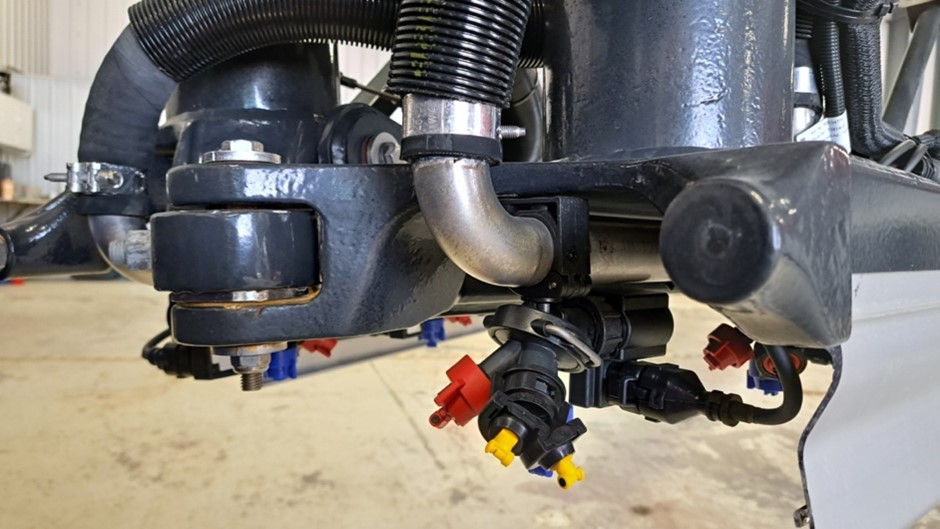

A section of a recirculating boom. Here, the sweep at the end of the boom replaces a traditional boom end cap, making priming and flushing easier.

Another shot of a recirculating boom where the sweep is more evident.

Nozzle check

Always physically double check your nozzles. They are a wear part and must be regularly replaced, usually every 30,000 to 50,000 acres. Not all nozzles are in use all the time, so just add up acres sprayed on each nozzle and do the math.

A flow meter check, not a visual check, is also non-negotiable. Measure the flow of each nozzle and set the pressure to a known pressure reading to avoid common pressure drops.

“You should know how the pressure is reading in the cab, which is usually measured at the centre rack, and compare it to the pressure reading at the nozzles. That’s actually pretty important because the pressure drop on pulse width modulation (PWM) systems might be up to 10 or 15 psi,” says Wolf.

To better compare cab versus nozzle pressure readings, he suggests investing in a cheap nozzle cap-mounted pressure gauge. If, for instance, a nozzle reads 5 psi less on the gauge than it does in the cab, you’ll know you’ll need to up the cab reading by 5 psi to compensate.

Double check for restrictions in screens, which is also a question of flow. The bigger the boom, the more likely there are issues. “If you have a single nozzle that is much higher in flow than the other ones, possibly it’s been damaged by an improper cleaning, or somebody was in a hurry and that should be replaced.”

More options are coming to nozzles, as well. Because PWM systems greatly improve accuracy and lower input bills, they’ve become increasingly common with more companies offering these nozzles. There used to only be two suppliers in Canada, but now there are five.

Smart spraying

Green-on-brown spraying continues to gain momentum and Wolf says farmers are buying the tech as fast as manufacturers can produce it. “They are selling by the dozens and that’s a pretty big number, actually, for something that is new and exciting,” says Wolf.

Canada’s most widely used system is still Quadro by WEED-IT, although John Deere has made a push into the space with its See & Spray Select system, operated via cameras and sensors.

For green-on-green spray technology, there are only a handful of options in Western Canada, and they are being watched closely for their efficacy. “The success or failure of those farmers is going to be very important,” says Wolf.

The focus of green-on-green, driven by AI, has been in row crops in the U.S., with soybeans, corn, and cotton receiving most of the attention for algorithm development. Bilberry, recently acquired by Trimble and available on Agrifac, has focused on Canadian cereal, oilseed and pulse crops.

The appeal of drones

Drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), continue to sprint toward the starting line in Canada, although the Pest Management Regulatory Agency has not yet announced any product registrations for UAV application.

Wolf believes the technology will likely stay niche but contends it can serve valuable logistical purposes.

He believes industrial herbicides may be the first approved use for rights of way, rangeland and brush areas, followed by fungicides in corn. As tar spot disease continues to spread, UAVs are ideal to provide complete coverage deeper into the canopy.

UAVs still have a number of issues: they do not cover a wide swath, they are labour intensive and they do not create a reliably uniform swath deposit. The likeliest uses are patch spraying and perhaps finishing up a nagging 10 to 20 acres left due to inclement weather.

One of the biggest drawbacks of UAVs remains carrying capacity. The largest can carry 40 litres, which sounds impressive until you remember that that equates to less than five acres at two gallons/ac. As UAVs increase in size and payload, secondary issues arise since larger aircraft require a more skilled pilot to manage good spray deposition and mitigate liabilities.

“These drones are now capable of causing significant harm to other people or even to property,” says Wolf. “If you don’t fly them well, responsibly or professionally, you may pose a hazard to other people.”

Season in review

Once your spraying season draws to a close, Wolf doesn’t recommend a 140-point inspection — although he’s not opposed to it. He simply encourages introspection.

“Reflect on the season; what went well and what went not so well and where you need to make changes,” he says. “It might be a winter project, so reflect now and commit to making those improvements when there’s still time.”