The phrase “up and to the right” is usually associated with investment portfolios and their jagged but steadily rising income graphs. The same can be said of potato production in Alberta, which has methodically plodded upward to its current day status of potato powerhouse.

For instance, in 2023, Alberta contributed 25 per cent to Canada’s entire potato pile, beating out Manitoba and Prince Edward Island for top potato dog status.

So how did that happen? Plenty of land with distinct geographies, a conducive climate and access to irrigation are part of the story. So is the influx of major potato processors to southern Alberta, the stability and financial heft they bring, and growers’ willingness to adjust what they produce to meet demand.

Chicken or egg: the transformation of an industry

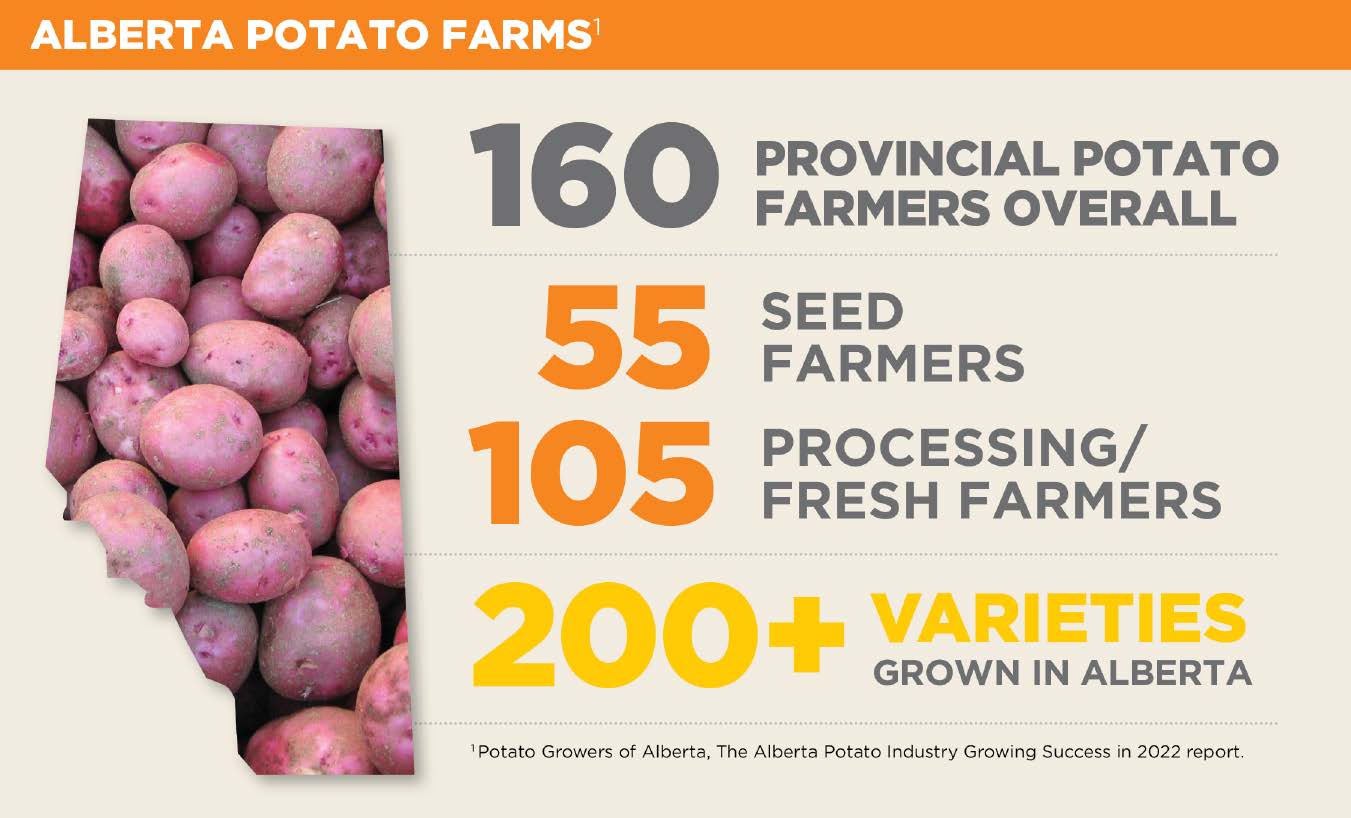

Over the last 25 years, potato production in Alberta has just about doubled from 43,000 seeded acres in 1999 to 80,100 in 2023. There are 160 potato farmers (and counting) in the province and the kind of potatoes grown has also undergone a shift. Before McCain set up shop near Coaldale at the turn of the millennium, Alberta produced mostly seed potatoes or fresh potatoes, with a small amount of processing potatoes, primarily used for french fries.

Since then, five other major processors have joined the party. Today, McCain Foods Canada is joined by Cavendish Farm Corporation, Shearer Foods, PepsiCo Inc., Lamb Weston Inc. and Old Dutch Foods Ltd., all of which operate out of southern Alberta and produce everything from french fries to chips to tater tots and more.

While this momentum may surprise some, it’s no shock to Terence Hochstein, executive director of the Potato Growers of Alberta (PGA). “It’s not starting to become a viable crop choice, it always has been a viable crop choice,” he says. “Alberta growers produce some of the best potato crops in the world and that produces some of the best french fries in the world. The industry wants to be a part of that.”

Location, location, location

Part of what makes southern Alberta a prime destination for potato production is the environment. It boasts strong northern vigour, thanks to its trademark hot days, cool nights, high-quality soil and its 110- to 130-day growing season.

As well, Alberta has two unique potato geographies. The north zone, essentially Calgary northward to Edmonton and surrounding area, is almost entirely for seed production whereas southern Alberta is almost entirely in commercial production for chips and fries. It’s a luxury scenario in the fight against disease.

“That physical separation in distance makes a huge difference for the seed isolation,” says Hochstein. “It allows them to grow (seed potatoes) in an environment that is not subject to potential disease. On the commercial side, you can get away with a little bit of disease and it’s not a factor. But you get that virus in a seed crop and it’s devastating. I mean, it will kill a crop.”

Westward-ho!

Hochstein has watched over the years as the potato power balance has shifted from East to West and says it’s plain to see why. “There’s only so many square feet in P.E.I. or New Brunswick, same with Maine,” he says. “There are more and more acres in the West that are suitable to produce potatoes and specialty crops.”

L to R: Nakamura Farms’ agronomist Paige Fletcher, Ryland and Lyndon Nakamura and Georges Dion from Frito Lay Canada, at the recent 2024 Potato Expo in Austin, TX. The brothers, who farm 2,100 acres of potatoes in southern Alberta, were named the 2023 PepsiCo Frito Lay Grower of the Year for North America. The first ever Canadian winners, the Nakamuras farm in a highly competitive area in southern Alberta where potatoes have never been more popular.

It helps that southern Alberta is home to a large and well-established irrigation system ideal for growing a water intensive crop in a naturally arid region. Under irrigation, farmers here can produce processing potatoes every four to five years, or longer, and, with water on demand, those crops are of higher yield and quality than those grown on dryland.

The value-added aspect of Alberta’s potato industry makes it a standout in a province where almost all other crops are exported as raw commodities, while potatoes are one of the very few crops that leave Alberta in a ready-made state. Indeed, a recent PGA report concluded that Alberta potatoes contribute $2.87 billion to the federal economy, with $2.31 billion of that value staying in the province.

New generation of farmers

The industry’s rapid growth and vertical integration has attracted a new generation of growers, many building on farms started by their parents and grandparents. Indeed, the average age of an Alberta potato farmer is 48, a full eight years younger than the average age of crop farmers in the province.

Farmers like brothers Ryland and Lyndon Nakamura, who operate Nakamura Farms north of Taber in southern Alberta. Each year they crop 2,100 acres of processing potatoes (in a 1-in-4 rotation) for five of the six major processors in the area.

While Ryland cannot deny the booming business of potatoes in Alberta, it does come with some baggage. An irrigated quarter-section in his area runs about $4 million, and inputs are always on the rise, too. And yet, they are contending with new growers moving in and outbidding them.

“It’s huge here now,” says Ryland, 39. “When I started, people my age never farmed potatoes. Ten years later, there’s a whole bunch of guys my age, that are the younger generation, that are farming now because they’ve expanded so much on the potato side.”

This year, the Nakamuras will plant seven different potato varieties, all of which were selected last year in conjunction with the processors. It creates a level of predictability for both parties.

“It gives us time to plan,” says Paige Fletcher, the farm’s in-house agronomist. “You always want to be planning at least a year in advance for your (crop) rotation, your chemical rotation, your fertilizer/manure applications. It helps having an idea of what you’re going to be growing next year and some stability behind it — the whole potato industry in southern Alberta is really good at that. The processors are really hands-on with the growers, making sure everybody knows where they stand and what to expect.”

Together, they pick varieties best suited to resist potato early dying complex and late blight, although, due to a dry stretch over the last few years, there have been zero issues with late blight.

Major processors carry their own proprietary seeds and the Nakamuras grow many of them, especially for Frito-Lay. This past year, due to their commitment to quality, traceability and meticulous farming practices, they were awarded the 2023 PepsiCo Frito Lay Grower of the Year for North America — the second Canadian farmers to be awarded the accolade.

Part of what helped the Nakamuras earn the award is their detailed record keeping, which includes everything from planting, spraying and harvest dates to the type and amount of inputs applied to when a pivot is activated and for how long — if it can be tracked, it is. They also track green house gas emissions from machinery, electrical usage during storage and more.

“It was a good experience and nice to have a pat on the back once in a while, and knowing that someone is seeing your hard work,” Ryland says, adding the award was shared by everybody at the farm, not just he and Lyndon. “We thanked the whole staff because they’re a part of it, too.”

Executive director of the Potato Growers of Alberta, Terence Hochstein sees the rise in potato acres across the province as a good news story for farmers. Farmland, potato value and value-added opportunities for farmers remain strong.

The team likes the high degree of accountability sought by processors and say it motivates them to stay at the top of their game. “If there’s a reason why some spuds go in or out of the bin not looking perfectly, then you know you can dig back in your records and see what you can do better next year,” says Fletcher.

This year will be a challenge, as always. With an El Niño winter and relatively light snowpack, the farm has a current water allocation of eight inches, or half of what is typically required to grow a crop. “That’s scary because last year we used about 20 inches because we only had an inch-and-a-half of rain all growing season,” says Ryland.

The Nakamuras are here to stay, even though the ever-competitive nature of potatoes in Alberta has created challenges. “There’s definitely some monetary things entering the conversation (about) the future of the farm. It’s not just, ‘can we grow it?’” says Ryland. “Business is a lot harder with the price of land, but we are willing to rent or buy if the opportunity comes.”

$PUD$

You might not think it, but potatoes are big business. How big? Consider that spuds contributed $2.87 billion to Canada’s economy in 2022 and, of that, $2.31 billion stays in Alberta.

Indeed, Alberta’s potato industry adds $1.3 billion to Canada’s GDP and $1 billion to Alberta’s.

Comparing the GDP per agricultural acre of Canada’s 2022 agri-food system, Alberta’s potato industry contributes 19.5 times the GDP per acre. This is due to the high agricultural productivity of potato production paired with a high level of value-add processing and packing within the province.

Made in Alberta

There are seven major value-added processors operating in Alberta — six in the south and one, The Little Potato Company, in Nisku, just south of Edmonton. Their cumulative investments have been sizeable to say the least. Here are four of the most recent:

McCain announced in 2023 that it plans to double the size of its plant at Coaldale, making this the single largest investment in the company’s 65-year history. That project alone will create an additional 260 full-time jobs on top of its 225 existing ones. The original plant opened in 2000 with a $93 million price tag.

In December 2023, The Little Potato Company turned the lights on at its new Nisku facility. The $40 million plant came about as the result of the province’s newly introduced Agri-Processing Investment Tax Credit, which gave the company a 12 per cent kickback on its capital expenditures. The new facility will nearly double the company’s production, from 65 million to 125 million pounds of fresh potatoes.

In 2022, Super-Pufft Snack Foods (Shearer Foods) opened an all-new $50 million processing facility in Airdrie, just north of Calgary. The plant is said to process 78,000 tonnes of potatoes annually and runs 24/7.

In 2019, Cavendish Farms began operating its new Lethbridge facility (replacing an older plant), an investment worth $430 million.