Canola producers across Western Canada should be aware of the threat that Sclerotinia stem rot, also known as white mould, poses to their crop. It is the single most destructive disease of canola on the Prairies, and the greatest thief to yield potential. When conditions are favourable for the disease, yield losses can exceed 50 percent in individual fields and 10 to 15 percent across large areas. In 2016, white mould occurred across Western Canada, with over 90 percent of fields infected and yield losses between seven to 15 percent.1,2

Managing white mould can be challenging because the disease system is complex. The disease is highly influenced by environmental conditions, particularly moisture, and favoured by cropping strategies that promote high yield in dense canopies. Moreover, the pathogen can survive and remain viable in the soil for five years or more. The pathogen also infects over 400 plant species in addition to canola, including many grown in Western Canada like sunflowers, beans, lentils, peas, mustard and common broadleaf weeds such as shepherd’s purse, thistles, stinkweed, chickweed, hemp-nettle, false ragweed, narrow-leafed hawk’s beard, and others.2,3 The abundance of host plants in Western Canada makes the disease even more likely to be present.

Managing Sclerotinia stem rot requires understanding key aspects of the disease system. Understanding the disease and how it develops enables effective decision making with available management tools.

Pathogen Biology and Disease Cycle

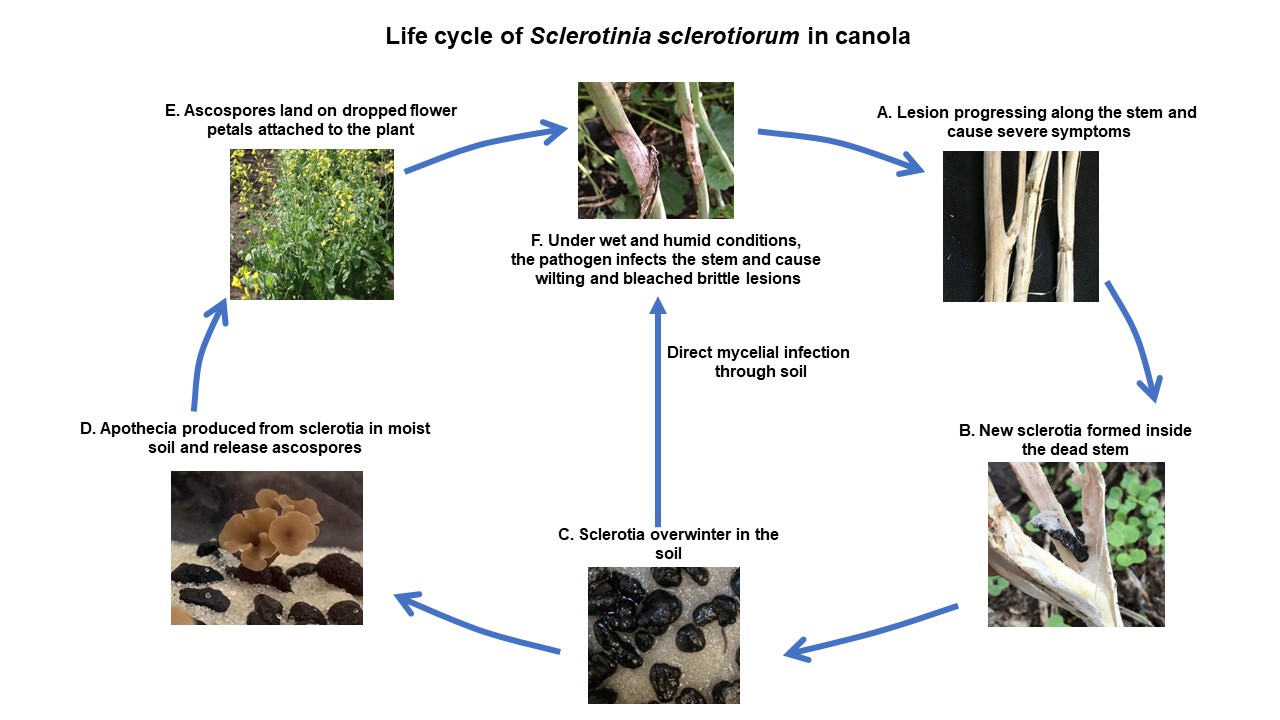

White mould is caused by the fungal pathogen, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary. The fungus lives both on and in infected canola plants as a white, fluffy mycelium that later forms dense black masses of fungal cell structures known as sclerotia (Figure 1B,C). These sclerotia fall to the ground during harvest and allow the fungus to overwinter and remain viable in the soil for five years or more in the absence of a host plant.2 This long-term survival mechanism is one reason why white mould can be a persistent problem for producers.

From the soil, sclerotia infect canola plants in the summer. Typically, sclerotia germinate to produce mushroom-like fruiting structures called apothecia that can extend to the soil surface. During periods of prolonged moist soil conditions (10 days above the wilting point or greater) and moderate to warm temperatures (15 to 25oC), apothecia develop and produce millions of ascospores that then are windblown to infect aerial portions of canola plants.2

Ascospores do not infect leaves and stems directly. They first infect flowers, fallen petals or even pollen on the stems and leaves. Fallen flower petals that are lodged in leaf axils on stems are often sites of initial infection. These plant parts provide the sources of nutrition required for the fungal spores to germinate, grow and eventually invade the plant. Water on plant surfaces and 100 percent humidity are required for ascospore infection to occur.2 In almost all cases, Sclerotinia infections in canola occur from ascospores. It is possible for sclerotia to produce mycelium that can infect plants directly, particularly through roots, but this is rare.5

Once infection takes place, plant tissues die, forming necrotic lesions. Infection can spread from leaves and stems as the fungus mycelium grows within the plant. Toward the end of the growing season, new sclerotia are formed inside dead stems, fall to the ground during harvest, and the disease cycle is repeated.

Figure 1. Lifecycle and symptoms of S. sclerotiorum in Canola. Image courtesy of Xuehua Zhang, Senior Scientist, Plant Health, Bayer Crop Science.

Figure 1. Lifecycle and symptoms of S. sclerotiorum in Canola. Image courtesy of Xuehua Zhang, Senior Scientist, Plant Health, Bayer Crop Science.

Timing and Environmental Conditions for Disease

Primary infection occurs during flowering, although in Western Canada, apothecia can appear as early as June and continue to develop until late September.2 The critical stage for damaging disease development is from early to full bloom. Rarely do apothecia appear in fields before plants are at the bud stage and seldom does infection develop before the mid-flowering stage. Good weather for canola growth is also good weather for initial pathogen infection and disease development. Environmental conditions conducive to sclerotia germination, ascospore production and pathogen growth, include:2,4

- One to two inches of rain or irrigation within one to two weeks of flowering.

- Prolonged soil moisture (10 days or more above the wilting point).

- Temperatures of 15 to 25oC.

These conditions occur as the crop canopy closes, shading the soil surface. Humid conditions and temperatures between 20 to 25oC are ideal for lesion development after initial infection. Although infection and lesion development will slow or stop with dry, warmer conditions (infection does not occur when temperatures are above 30oC), disease development can resume with the return of favorable conditions.2

Identifying the Disease in the Field

White mould develops late in the growing season with the first visual symptoms appearing by the end of flowering. If the disease occurs during flowering and environmental conditions are favorable, then there is a strong likelihood of further disease development.4

Within two to three weeks after initial infection on dead flower petals, lesions appear as water-soaked spots or areas of brown to grey discoloration on leaves and stems, particularly around leaf axils (Figure 1F). As infection develops on the stems, lesions enlarge and turn grey-white in color. Faint concentric patterns may also be noticed on expanded lesions (Figure 1F).2 As lesions continue to expand, stems may become girdled causing plants to wilt and ripen prematurely. As infection further develops, stems will bleach and tend to shred (Figure 1A). Premature death of the plant may occur, while severely infected plants often lodge and shatter at swathing. White mould has some characteristic and identifiable signs associated with disease development, including:

- Brown or bleached necrotic lesions appear around penetration sites and spread to other parts of the plant.

- White cottony mycelium of the fungus on both the inside and outside of infected stems.

- Hard, black sclerotia on the outer surface of diseased tissue but can be observed inside infected tissue as well (Figure 1B,C).

- Sclerotia can be small and oval, similar to canola seed, or larger and irregular in shape (up to two centimeters or 0.8 inch long).2

Key Aspects of Disease Management

Most canola cultivars are susceptible to white mould, even if at varying levels, when environmental conditions are favorable. Therefore, management decisions are vital at different stages of crop development to minimize the risk of infection. Effective management requires the use of multiple, integrated strategies. There are some key management practices that can influence disease development, including chemical control (fungicides), host resistance, and crop rotation.

Fungicides: Foliar fungicides provide an effective option for the management of white mould on canola when the risk of disease development is high. Because disease incidence and development are so dependent on environmental conditions around flowering, the timing and method of the fungicide application are critical. Scouting is necessary to assess conditions conducive for disease. If the field has a previous history of white mould and weather conditions have been wet for a couple of weeks prior to flowering, apply a foliar fungicide between 20 to 50 percent bloom, with optimum timing at 30 percent bloom.2,6 It is important that the fungicide application cover as many petals as possible and penetrates the canopy to protect leaf axils and bases from possible infection. To cover flower petals adequately, high water volumes should be considered. According to research at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, conventional flat fan nozzles, low-drift venturi nozzles, and hollow cone nozzles were effective at reducing disease severity.2

Refer to your Province’s Crop Protect Guides for a complete list of registered fungicides. Always consult with crop specialists and follow fungicide label recommendations.

Host Resistance: There are canola products in Canada with tolerance to sclerotinia stem rot, but none have complete resistance. These products have shown reduced severity to disease in trials with less lesion development on stems and other plant parts.2 Products with strong stems and a higher tendency to branch in growth reduce the likelihood of lodging and disease severity.6 When the risk of severe disease infection is present, a fungicide application may still be a good decision.

For help with tolerance and product selection, see the protocol developed by Dr. Lone Buchwaldt and the Pathology sub-committee of the Western Canada Canola/Rapeseed Recommending Committee:

https://www.canolacouncil.org/download/133/research/4945/CanolaResearchHub_WCC-RRC_2016_Buchwaldt

Crop Rotation: Crop rotation with nonhost crops (monocots like wheat, corn, barley, or grass) reduces the number of sclerotia in the soil. Because sclerotia remain viable for long periods of time, a minimum three-year rotation is required with a non-host.2,4,6,7

Other management practices that can influence the level of infection and the rate of disease spread include:

- Seeding and Row Spacing: Manipulating practices such as location selection, seeding rate, row spacing, nitrogen fertilizers, and canola product selection to minimize humidity within the plant canopy can lessen white mould incidence and severity.2,5,6

- Controlling Irrigation: Avoiding conditions that encourage periods of leaf wetness beyond 12 to 24 hours or during periods of high humidity, especially during flowering, can reduce the threat and impact of white mold.4,5,6

- Weed Control: Many common broadleaf weeds are hosts for S. sclerotiorum and can serve as sources of pathogen inoculum for canola, therefore, weed control is very important in minimizing disease.5

- Tillage: The effect of tillage on the management of white mould is unclear. Deep tillage can prevent germination of apothecia but deeply buried sclerotia survive well and may be returned to the soil surface or distributed across fields with subsequent tillage operations.5,7

- Harvest: Growers can lose up to one third of their crop to sclerotinia stem rot during swathing and suffer a downgrading of canola due to sclerotia in seed samples.2 In addition, the increases in sclerotia development during swathing can allow the pathogen to remain in the field after harvest. During forecasts for heavy rain events when disease is present in the field, do not swath.2

- Biological Control: There are biological products available to Canadian canola growers that can help suppress disease development. These products may be incorporated as part of a spray program that includes a conventional fungicide.2

Sources

1Arnason, R. 2018. Sclerotinia not a disease to ignore. The Western Producer. https://www.producer.com/crops/sclerotinia-not-disease-ignore/

2Canola Council of Canada. 2021. Canola Encyclopedia: Sclerotinia stem rot. https://www.canolacouncil.org/canola-encyclopedia/diseases/sclerotinia-stem-rot/

3Turkington, T.K., Kutcher, H.R., McLaren, D., and Rashid, K.Y. 2011. Managing sclerotinia in oilseed and pulse crops. Prairie Soils and Crops Journal vol 4:105-113.

4Paulitz, T., Schroeder, K., and Beard, L. 2015. Sclerotinia stem rot or white mold of canola. Washington State University Extension. Washington Oilseed Cropping Systems Series. FS188E

5Heffner Link, V., and Johnson, K.B. 2012. White Mold. The Plant Health Instructor. DOI:10.1094/PHI-I-2007-0809-01 https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/disandpath/fungalasco/pdlessons/Pages/WhiteMold.aspx

6Government of Saskatchewan. Sclerotinia Diseases. https://www.saskatchewan.ca/business/agriculture-natural-resources-and-industry/agribusiness-farmers-and-ranchers/crops-and-irrigation/disease/sclerotinia

7Kandel, H., Lubenow, L., Keene, C., and Knodel, J.J. Canola Production Field Guide (A1280, Reviewed Jan. 2019). North Dakota State State University. https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/publications/crops/canola-production-field-guide#section-96

Legal Statements

ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL DIRECTIONS. Performance may vary from location to location and from year to year, as local growing, soil and weather conditions may vary. Growers should evaluate data from multiple locations and years whenever possible and should consider the impacts of these conditions on the grower’s fields.

Bayer and Bayer Cross are registered trademarks of Bayer Group. Used under license. ©2021 Bayer Group. All rights reserved. 1026_S3_CA